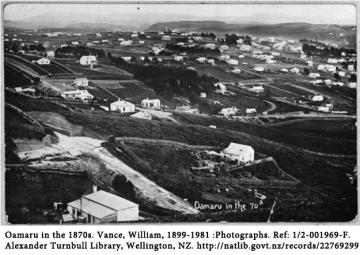

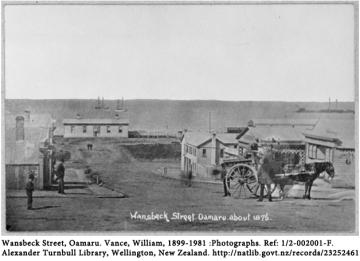

Emma arrived in Oamaru with her parents in January of 1862. This was a mere nine years after her uncle’s settlement there. In 1853, when John Lemon arrived, Oamaru was far from being a town — see the following account by from another early settler, Mr F. Every:

(from Mr Roberts’ very detailed history of Oamaru and North Otago, published in 1890)

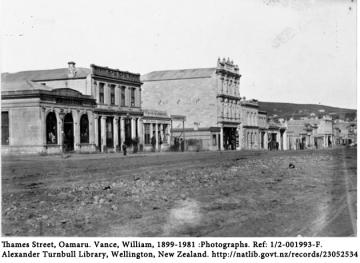

By the time Emma and her parents arrived, however, the town was growing fast, on the back of its port and the relative proximity of the gold-fields. Emma’s father, George Sumpter, was involved in both these operations —supplying stores to the miners, and becoming a stalwart of the Harbour Board.

Both George and Oamaru thrived. Mackay’s Almanac for 1865 says:

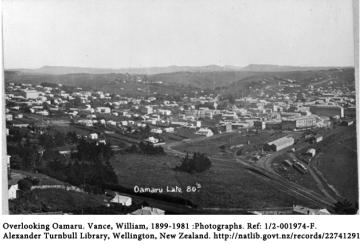

No township in the Province has shown so steady and satisfactory an advance during the last three years as Oamaru.

That same year, ‘telegraphic communication’ between Dunedin, Oamaru and Christchurch was completed.

By the end of 1867, Oamaru had 1376 residents, and received some £9452 in Customs revenue for the year, from 11 ships bringing imports to the value of £92,165. Wool to the value of £173,904 had been shipped out.

In the same way that George is in many ways representative of Oamaru, so Oamaru reflects the greater nation. Oamaru grew, and borrowed heavily to build the infrastructure they aspired to.

By the 1880s, NZ, Oamaru, and George, were all struggling.

References

“The History of Oamaru and North Otago, New Zealand, From 1853 to the end of 1889” W.H.S. Roberts. Published by Andrew Fraser, Oamaru; 1890.

“White Stone Country: The story of North Otago” by K.C. McDonald. Published by the North Otago Centennial Committee, 1962.